At GitHub Universe 2018, GitHub launched GitHub Actions in beta. Later in

August 2019, GitHub announced the expansion of GitHub Actions to include

Continuous Integration / Continuous Delivery (CI/CD). At Universe 2019,

GitHub

announced

that Actions are out of beta and generally available. I spent the last few

days, while I was taking some vacation during Thanksgiving, to explore GitHub

Actions for automation of Python projects.

With my involvement in the Gaphor project, we have a GUI

application to maintain, as well as two

libraries, a diagramming widget called

Gaphas, and we more recently took over

maintenance of a library that enables multidispatch and events called

Generic. It is important to have an

efficient programming workflow to maintain these projects, so we can spend more

of our open source volunteer time focusing on implementing new features and

other enjoyable parts of programming, and less time doing manual and boring

project maintenance.

In this blog post, I am going to give an overview of what CI/CD is, my previous

experience with other CI/CD systems, how to test and deploy Python applications

and libraries using GitHub Actions, and finally highlight some other Actions

that can be used to automate other parts of your Python workflow.

Overview of CI/CD

Continuous Integration (CI) is the practice of frequently integrating changes to

code with the existing code repository.

Continuous Delivery / Delivery (CD) then extends CI by making sure the software checked in

to the master branch is always in a state to be delivered to users, and

automates the deployment process.

For open source projects on GitHub or GitLab,

the workflow often looks like:

- The latest development is on the mainline branch called master.

- Contributors create their own copy of the project, called a fork, and then

clone their fork to their local computer and setup a development environment.

- Contributors create a local branch on their computer for a change they want

to make, add tests for their changes, and make the changes.

- Once all the unit tests pass locally, they commit the changes and push them

to the new branch on their fork.

- They open a Pull Request to the original repo.

- The Pull Request kicks off a build on the CI system automatically, runs

formatting and other lint checks, and runs all the tests.

- Once all the tests pass, and the maintainers of the project are good with

the updates, they merge the changes back to the master branch.

Either in a fixed release cadence, or occasionally, the maintainers then add a

version tag to master, and kickoff the CD system to package and release a new

version to users.

My Experience with other CI/CD Systems

Since most open source projects didn't want the overhead of maintaining their

own local CI server using software like Jenkins, the use of cloud-based or

hosted CI services became very popular over the last 7 years. The most

frequently used of these was Travis CI with Circle CI a close second. Although

both of these services introduced initial support for Windows over the last

year, the majority of users are running tests on Linux and macOS only. It is

common for projects using Travis or Circle to use another service called

AppVeyor if they need to test on Windows.

I think the popularity of Travis CI and the other similar services is based on

how easy they were to get going with. You would login to the service with your

GitHub account, tell the service to test one of your projects, add a YAML

formatted file to your repository using one of the examples, and push to the

software repository (repo) to trigger your first build. Although these services

are still hugely popular, 2019 was the year that they started to lose some of

their momentum. In January 2019, a company called Idera bought Travis CI. In

February Travis CI then

laid-off a lot

of their senior engineers and technical staff.

The 800-pound gorilla entered the space in 2018, when Microsoft bought GitHub

in June and then rebranded their Visual Studio Team Services ecosystem and

launched Azure Pipelines as a CI service in September. Like most of the popular

services, it was free for open source projects. The notable features of this

service was that it launched supporting Linux, macOS, and Windows, and it

allowed for 10 parallel jobs. Although the other services offer parallel

builds, on some platforms they are limited for open source projects, and I

would often be waiting for a server called an "agent" to be available with

Travis CI. Following the lay-offs at Travis CI, I was ready to explore other

services to use, and Azure Pipelines was the new hot CI system.

In March 2019, I was getting ready to launch version 1.0.0 of Gaphor after

spending a couple of years helping to update it to Python 3 and PyGObject. We

had been using Travis CI, and we were lacking the ability to test and package

the app on all three major platforms. I used this as an opportunity to learn

Azure Pipelines with the goal of being able to fill this gap we had in our

workflow.

My takeaways from this experience is that Azure Pipelines is lacking much of

the ease of use as compared to Travis CI, but has other huge advantages

including build speed and the flexibility and power to create complex

cross-platform workflows. Developing a complex workflow on any of these CI

systems is challenging because the feedback you receive takes a long time to

get back to you. In order to create a workflow, I normally:

- Create a branch of the project I am working on

- Develop a YAML configuration based on the documentation and examples available

- Push to the branch, to kickoff the CI build

- Realize that something didn't work as expected after 10 minutes of waiting

for the build to run

- Go back to step 2 and repeat, over and over again

One of my other main takeaways was that the documentation was often lacking

good examples of complex workflows, and was not very clear on how to use each

step. This drove even more trial and error, which requires a lot of patience as

you are working on a solution. After a lot of effort, I was able to complete a

configuration that tested Gaphor on Linux, macOS, and Windows. I also was able

to partially get the CD to work by setting up Pipelines to add the built dmg

file for macOS to a draft release when I push a new version tag. A couple of

weeks ago, I was also able build and upload Python Wheel and source

distribution, along with the Windows binaries built in

MSYS2.

Despite the challenges getting there, the result was very good! Azure Pipelines

is screaming fast, about twice as fast as Travis CI was for my complex

workflows (25 minutes to 12 minutes). The tight integration that allows testing

on all three major platforms was also just what I was looking for.

How to Test a Python Library using GitHub Actions

With all the background out of the way, now enters GitHub Actions. Although I

was very pleased with how Azure Pipelines performs, I thought it would be nice

to have something that could better mix the ease of use of Travis CI with the

power Azure Pipelines provides. I hadn't made use of any Actions before

trying to replace both Travis and Pipelines on the three Gaphor projects that

I mentioned at the beginning of the post.

I started first with the libraries, in order to give GitHub Actions a try with

some of the more straightforward workflows before jumping in to converting Gaphor

itself. Both Gaphas and Generic were using Travis CI. The workflow was pretty

standard for a Python package:

- Run lint using pre-commit to run

Black over the code base

- Use a matrix build to test the library using Python 2.7, 3.6, 3.7, and 3.8

- Upload coverage information

To get started with GitHub Actions on a project, go to the Actions tab on the

main repo:

Based on your project being made up of mostly Python, GitHub will suggest three

different workflows that you can use as templates to create your own:

- Python application - test on a single Python version

- Python package - test on multiple Python versions

- Publish Python Package - publish a package to PyPI using Twine

Below is the workflow I had in mind:

I want to start with a lint job that is run, and once that has successfully

completed, I want to start parallel jobs using the multiple versions of Python

that my library supports.

For these libraries, the 2nd workflow was the closest for what I was looking

for, since I wanted to test on multiple versions of Python. I selected the

Set up this workflow option. GitHub then creates a new draft YAML file based

on the template that you selected, and places it in the .github/workflows

directory in your repo. At the top of the screen you can also change the name

of the YAML file from pythonpackage.yml to any filename you choose. I called

mine build.yml, since calling this type of workflow a build is the

nomenclature I am familiar with.

As a side note, the online editor that GitHub has implemented for creating

Actions is quite good. It includes full autocomplete (toggled with Ctrl+Space),

and it actively highlights errors in your YAML file to ensure the correct

syntax for each workflow. These type of error checks are priceless due to the

long feedback loop, and I actually recommend using the online editor at this

point over what VSCode or Pycharm provide.

Execute on Events

The top of each workflow file are two keywords: name and on. The name sets

what will be displayed in the Actions tab for the workflow you are creating. If

you don't define a name, then the name of the YAML file will be shown as the

Action is running. The on keyword defines what will cause the workflow to be

started. The template uses a value of push, which means

that the workflow will be kicked off when you push to any branch in the

repo. Here is an example of how I set these settings for my libraries:

name: Build

on:

pull_request:

push:

branches: master

Instead of running this workflow on any push event, I wanted a build to happen

during two conditions:

- Any Pull Request

- Any push to the master branch

You can see how that was configured above. Being able to start a workflow on

any type of event in GitHub is extremely powerful, and it one of the advantages

of the tight integration that GitHub Actions has.

Lint Job

The next section of the YAML file is called jobs, this is where each main

block of the workflow will be defined as a job. The jobs will then be further

broken down in to steps, and multiple commands can be executed in each step.

Each job that you define is given a name. In the template, the job is named

build, but there isn't any special significance of this name. They also are

running a lint step for each version of Python being tested against. I decided

that I wanted to run lint once as a separate job, and then once that is

complete, all the testing can be kicked off in parallel.

In order to add lint as a separate job, I created a new job called lint

nested within the jobs keyword. Below is an example of my lint job:

jobs:

lint:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v1

- name: Setup Python

uses: actions/setup-python@v1

with:

python-version: '3.x'

- name: Install Dependencies

run: |

pip install pre-commit

pre-commit install-hooks

- name: Lint with pre-commit

run: pre-commit run --all-files

Next comes the runs-on keyword which defines which platform GitHub Actions

will run this job on, and in this case I am running on linting on the latest

available version of Ubuntu. The steps keyword is where most of the workflow

content will be, since it defines each step that will be taken as it is run.

Each step optionally gets a name, and then either defines an Action to use, or a

command to run.

Let's start with the Actions first, since they are the first two steps in my

lint job. The keyword for an Action is uses, and the value is the action repo

name and the version. I think of Actions as a library, a reusable step that I

can use in my CI/CD pipeline without having to reinvent the wheel. GitHub

developed these first two Actions that I am making use of, but you will see

later that you can make use of any Actions posted by other users, and even

create your own using the Actions SDK and some TypeScript. I am now convinced

that this is the "secret sauce" of GitHub Actions, and will be what makes this

service truly special. I will discuss more about this later.

The first two Actions I am using clones a copy of the code I am testing from my

repo, and sets up Python. Actions often use the with keyword for the

configuration options, and in this case I am telling the setup-python action

to use a newer version from Python 3.

- uses: actions/checkout@v1

- name: Setup Python

uses: actions/setup-python@v1

with:

python-version: '3.x'

The last two steps of the linting job are using the run keyword. Here I am

defining commands to execute that aren't covered by an Action. As I mentioned

earlier, I am using pre-commit to run Black over the project and check the code

formatting is correct. I have this broken up in to two steps:

- Install Dependencies - installs pre-commit, and the pre-commit hook

environments

- Lint with pre-commit - runs Black against all the files in the repo

In the Install Dependencies step, I am also using the pipe operator, "|",

which signifies that I am giving multiple commands, and I am separating each

one on a new line. We now should have a complete lint job for a Python library,

if you haven't already, now would be a good time to commit and push your

changes to a branch, and check the lint job passes for your repo.

Test Job

For the test job, I created another job called test, and it also uses

the ubuntu-latest platform for the job. I did use one new keyword here called

needs. This defines that this job should only be started once the lint job has

finished successfully. If I didn't include this, then the lint job and all the

other test jobs would all be started in parallel.

test:

needs: lint

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

Next up I used another new keyword called strategy. A strategy creates a build

matrix for your jobs. A build matrix is a set of different configurations of the

virtual environment used for the job. For example, you can run a job against

multiple operating systems, tool version, or in this case against different

versions of Python. This prevents repetitiveness because otherwise you would

need to copy and paste the same steps over and over again for different versions

of Python. Finally, the template we are using also had a max-parallel keyword

which limits the number of parallel jobs that can run simultaneously. I am only

using four versions of Python, and I don't have any reason to limit the number

of parallel jobs, so I removed this line for my YAML file.

strategy:

matrix:

python-version: [2.7, 3.6, 3.7, 3.8]

Now on to the steps of the job. My first two steps, checkout the sources and

setup Python, are the same two steps as I had above in the lint job. There is

one difference, and that is that I am using the ${{ matrix.python-version }}

syntax in the setup Python step. I use the {{ }} syntax to define an

expression. I am using a special kind of expression called a context, which is

a way to access information about a workflow run, the virtual environment,

jobs, steps, and in this case the Python version information from the matrix

parameters that I configured earlier. Finally, I use the $ symbol in front of

the context expression to tell Actions to expand the expression in to its

value. If version 3.8 of Python is currently running from the matrix, then ${{

matrix.python-version }} is replaced by 3.8.

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v1

- name: Set up Python ${{ matrix.python-version }}

uses: actions/setup-python@v1

with:

python-version: ${{ matrix.python-version }}

Since I am testing a GTK diagramming library, I need to also install some

Ubuntu dependencies. I use the > symbol as YAML syntax to ignore the newlines

in my run value, this allows me to execute a really long command while keeping

my standard line length in my .yml file.

- name: Install Ubuntu Dependencies

run: >

sudo apt-get update -q && sudo apt-get install

--no-install-recommends -y xvfb python3-dev python3-gi

python3-gi-cairo gir1.2-gtk-3.0 libgirepository1.0-dev libcairo2-dev

For my projects, I love using Poetry for managing my Python dependencies.

See my other article on Python Packaging with Poetry and

Briefcase for more

information on how to make use of Poetry for your projects. I am using a custom

Action that Daniel Schep created that installs

Poetry. Although installing Poetry manually is pretty straightforward, I really

like being able to make use of these building blocks that others have created.

Although you should always use a Python virtual environment while you are

working on a local development environment, they aren't really needed since

the environment created for CI/CD is already isolated and won't be reused. This

would be a nice improvement to the install-poetry-action, so that the

creation of virtualenvs are turned off by default.

- name: Install Poetry

uses: dschep/install-poetry-action@v1.2

with:

version: 1.0.0b3

- name: Turn off Virtualenvs

run: poetry config virtualenvs.create false

Next we have Poetry install the dependencies using the poetry.lock file using

the poetry install command. Then we are to the key step of the job, which is

to run all the tests using Pytest. I preface the pytest command with

xvfb-run because this is a GUI library, and many of the tests would fail

because there is no display server, like X or Wayland, running on the CI runner.

The X virtual framebuffer (Xvfb) display server is used to perform all the

graphical operations in memory without showing any screen output.

- name: Install Python Dependencies

run: poetry install

- name: Test with Pytest

run: xvfb-run pytest

The final step of the test phase is to upload the code coverage information. We

are using Code Climate for analyzing coverage,

because it also integrates a nice maintainability score based on things like

code smells and duplication it detects. I find this to be a good tool to help

us focus our refactoring and other maintenance efforts.

Coveralls and Codecov are good

options that I have used as well. In order for the code coverage information to

be recorded while Pytest is running, I am using the

pytest-cov Pytest plugin.

- name: Code Climate Coverage Action

uses: paambaati/codeclimate-action@v2.3.0

env:

CC_TEST_REPORTER_ID: 195e9f83022747c8eefa3ec9510dd730081ef111acd99c98ea0efed7f632ff8a

with:

coverageCommand: coverage xml

CD Workflow - Upload to PyPI

I am using a second workflow for my app, and this workflow would actually be

more in place for a library, so I'll cover it here. The Python Package Index

(PyPI) is normally how we share libraries across Python projects, and it is

where they are installed from when you run pip install. Once I am ready to

release a new version of my library, I want the CD pipeline to upload it to

PyPI automatically.

If you recall from earlier, the third GitHub Action Python workflow template was

called Publish Python Package. This template is close to what I needed for my

use case, except I am using Poetry to build and upload instead of using

setup.py to build and Twine to upload. I also used a slightly different event

trigger.

on:

release:

types: published

This sets my workflow to execute when I fully publish the GitHub release. The

Publish Python Package template used the event created instead. However, it

makes more sense to me to publish the new version, and then upload it to PyPI,

instead of uploading to PyPI and then publishing it. Once a version is uploaded

to PyPI it can't be reuploaded, and new version has to be created to upload

again. In other words, doing the most permanent step last is my preference.

The rest of the workflow, until we get to the last step, should look very

similar to the test workflow:

jobs:

deploy:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v1

- name: Set up Python

uses: actions/setup-python@v1

with:

python-version: '3.x'

- name: Install Poetry

uses: dschep/install-poetry-action@v1.2

with:

version: 1.0.0b3

- name: Install Dependencies

run: poetry install

- name: Build and publish

run: |

poetry build

poetry publish -u ${{ secrets.PYPI_USERNAME }} -p ${{ secrets.PYPI_PASSWORD }}

The final step in the workflow uses the poetry publish command to upload the

Wheel and sdist to PyPI. I defined the secrets.PYPI_USERNAME and

secrets.PYPI_PASSWORD context expressions by going to the repository

settings, then selecting Secrets, and defining two new encrypted environmental

variables that are only exposed to this workflow. If a contributor created a

Pull Request from a fork of this repo, the secrets would not be passed to any

of workflows started from the Pull Request. These secrets, passed via the -u

and -p options of the publish command, are used to authenticate with the

PyPI servers.

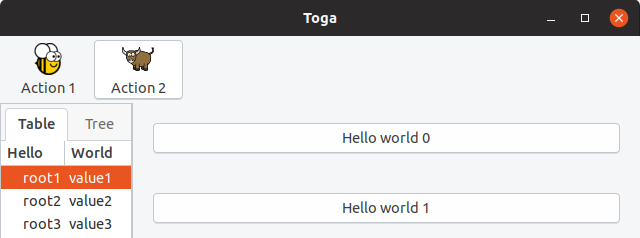

At this point, we are done with our configuration to test and release a

library. Commit and push your changes to your branch, and ensure all the steps

pass successfully. This is what the output will look like on the Actions tab in

GitHub:

I have posted the final version of my complete GitHub Actions workflows for a

Python library on the Gaphas

repo.

How to Test and Deploy a Python Application using GitHub Actions

My use case for testing a cross-platform Python Application is slightly

different from the previous one we looked at for a library. For the library, it

was really important we tested on all the supported versions of Python. For an

application, I package the application for the platform it is running on with

the version of Python that I want the app to use, normally the latest stable

release of Python. So instead of testing with multiple versions of Python, it

becomes much more important to ensure that the tests pass on all the platforms

that the application will run on, and then package and deploy the app for each

platform.

Below are the two pipelines I would like to create, one for CI and one for CD.

Although you could combine these in to a single pipeline, I like that GitHub

Actions allows so much flexibility in being able to define any GitHub event to

start a workflow. This tight integration is definitely a huge bonus here, and it

allows you to make each workflow a little more atomic and understandable. I

named my two workflows build.yml for the CI portion, and release.yml for the

CD portion.

Caching Python Dependencies

Although the lint phase is the same between a library and an application, I am

going to add in one more optional cache step that I didn't include earlier for

simplification:

- name: Use Python Dependency Cache

uses: actions/cache@v1.0.3

with:

path: ~/.cache/pip

key: ${{ runner.os }}-pip-${{ hashFiles('**/poetry.lock') }}

restore-keys: ${{ runner.os }}-pip-

It is a good practice to use a cache to store information that doesn't often

change in your builds, like Python dependencies. It can help speed up the build

process and lessen the load on the PyPI servers. While setting this up, I also

learned from the Travis CI

documentation

that you should not cache large files that are quick to install, but are slow

to download like Ubuntu packages and docker images. These files take as long to

download from the cache as they do from the original source. This explains why

the cache action doesn't have any examples on caching these types of files.

The caches work by checking if a cached archive exists at the beginning of the

workflow. If it exists, it downloads it and unpacks it to the path location.

At the end of the workflow, the action checks if the cache previously existed,

if not, this is called a cache miss, and it creates a new archive and uploads it

to remote storage.

A few configurations to notice, the path is operating system dependent because

pip stores its cache in different locations. My configuration above is for

Ubuntu, but you would need to use ~\AppData\Local\pip\Cache for Windows and

~/Library/Caches/pip for macOS. The key is used to determine if the correct

cache exists for restoring and saving to. Since I am using Poetry for

dependency management, I am taking the hash of the poetry.lock file and

adding it to end of a key which contains the context expression for the

operating system that the job is running on, runner.os, and pip. This will

look like

Windows-pip-45f8427e5cd3738684a3ca8d009c0ef6de81aa1226afbe5be9216ba645c66e8a,

where the end is a long hash. This way if my project dependencies change, my

poetry.lock will be updated, and a new cache will be created instead of

restoring from the old cache. If you aren't using Poetry, you could also use

your requirements.txt or Pipfile.lock for the same purpose.

As we mentioned earlier, if the key doesn't match an existing cache, it's

called a cache miss. The final configuration option called restore-keys is

optional, and it provides an ordered list of keys to use for restoring the

cache. It does this by sequentially searching for any caches that partially

match in the restore-keys list. If a key partially matches, the action

downloads and unpacks the archive for use, until the new cache is uploaded at

the end of the workflow.

Test Job

Ideally, it would be great to use a build matrix to test across platforms. This

way you could have similar build steps for each platform without repeating

yourself. This would look something like this:

runs-on: ${{ matrix.os }}

strategy:

matrix:

os: [ubuntu-latest, windows-latest, macOS-latest]

steps:

- name: Install Ubuntu Dependencies

if: matrix.os == 'ubuntu-latest'

run: >

sudo apt-get update -q && sudo apt-get install

--no-install-recommends -y xvfb python3-dev python3-gi

python3-gi-cairo gir1.2-gtk-3.0 libgirepository1.0-dev libcairo2-dev

- name: Install Brew Dependencies

if: matrix.os == 'macOS-latest'

run: brew install gobject-introspection gtk+3 adwaita-icon-theme

Notice the if keyword tests which operating system is currently being used in

order to modify the commands for each platform. As I mentioned earlier, the GTK

app I am working on, requires MSYS2 in order to test

and package it for Windows. Since MSYS2 is a niche platform, most of the steps

are unique and require manually setting paths and executing shell scripts. At

some point maybe we can get some of these unique parts better wrapped in an

action, so that when we abstract up to the steps, they can be more common

across platforms. Right now, using a matrix for each operating system in my

case wasn't easier than just creating three separate jobs, one for each

platform.

If you are interested in a more complex matrix setup, Jeff Triplett

posted his

configuration for running five different Django versions against five different

Python versions.

The implementation of the three test jobs is similar to the library test job

that we looked at earlier.

test-linux:

needs: lint

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

...

test-macos:

needs: lint

runs-on: macOS-latest

...

test-windows:

needs:lint

runs-on: windows-latest

The other steps to install the dependencies, setup caching, and test with Pytest

were identical.

CD Workflow - Release the App Installers

Now that we have gone through the CI workflow for a Python application, on to

the CD portion. This workflow is using different event triggers:

name: Release

on:

release:

types: [created, edited]

GitHub has a Release tab that is built in to each repo. The deployment workflow

here is started if I create or modify a release. You can define multiple events

that will start the workflow by adding them as a comma separated list. When I

want to release a new version of Gaphor:

- I update the version number in the

pyproject.toml, commit the change, add

a version tag, and finally push the commit and the tag.

- Once the tests pass, I edit a previously drafted release to point the tag to

the tag of the release.

- The release workflow automatically builds and uploads the Python Wheel and

sdist, the macOS dmg, and the Windows installer.

- Once I am ready, I click on the GitHub option to Publish release.

In order to achieve this workflow, first we create a job for Windows and macOS:

upload-windows:

runs-on: windows-latest

...

upload-macos:

runs-on: macOS-latest

...

The next steps to checkout the source, setup Python, install dependencies,

install poetry, turn off virtualenvs, use the cache, and have poetry install the

Python dependencies are the exact same as the application Test Job above.

Next we build the wheel and sdist, which is a single command when using Poetry:

- name: Build Wheel and sdist

run: poetry build

Our packaging for Windows is using custom shell scripts that run

PyInstaller to package up the app, libraries, and

Python, and makensis to create a Windows installer. We are also using a custom

shell script to package the app for macOS. Once I execute the scripts to

package the app, I then upload the release assets to GitHub:

- name: Upload Assets

uses: AButler/upload-release-assets@v2.0

with:

files: 'macos-dmg/*dmg;dist/*;win-installer/*.exe'

repo-token: ${{ secrets.GITHUB_TOKEN }}

Here I am using Andrew Butler's

upload-release-assets

action. GitHub also has an action to perform this called

upload-release-asset, but

at the time of writing this, it didn't support uploading multiple files using

wildcard characters, called glob patterns. secrets.GITHUB_TOKEN is another

context expression to get the access token to allow Actions permissions to

access the project repository, in this case to upload the release assets to a

drafted release.

The final version of my complete GitHub Actions workflows for the

cross-platform app are posted on the Gaphor

repo.

Future Improvements to My Workflow

I think there is still some opportunity to simplify the workflows that I have

created through updates to existing actions or creating new actions. As I

mentioned earlier, it would be nice to have things at a maturity level so that

no custom environment variable, paths, or shell scripts need to be run. Instead,

we would be building workflows with actions as building blocks. I wasn't

expecting this before I started working with GitHub Actions, but I am sold that

this would be immensely powerful.

Since GitHub recently released CI/CD for Actions, many of the GitHub provided

actions could use a little polish still. Most of the things that I thought of

for improvements, already had been recognized by others with Issues opened for

Feature requests. If we give it a little time, I am sure these will be improved

soon.

I also said that one of my goals was to release to the three major platforms,

but if you were paying attention in the last section, I only mentioned Windows

and macOS. We are currently packaging our app using Flatpak for Linux and it is

distributed through FlatHub. FlatHub does have an

automatic build system, but it requires manifest files stored in a special

separate FlatHub repo for the app. I also contributed to the Flatpak Builder

Tools in order to

automatically generate the needed manifest from the poetry.lock file. This

works good, but it would be nice in the future to have the CD workflow for my

app, kickoff updates to the FlatHub repo.

Bonus - Other Great Actions

Debugging with

tmate - tmate is

a terminal sharing app built on top of tmux. This great action allows you to

pause a workflow in the middle of executing the steps, and then ssh in to the

host runner and debug your configuration. I was getting a Python segmentation

fault while running my tests, and this action proved to be extremely useful.

Release Drafter - In

my app CD workflow, I showed that I am executing it when I create or edit a

release. The release drafter action drafts my next release with release notes

based on the Pull Requests that are merged. I then only have to edit the

release to add the tag I want to release with, and all of my release assets

automatically get uploaded. The PR

Labeler action goes along

with this well to label your Pull Requests based on branch name patterns like

feature/*.